Enjoy today

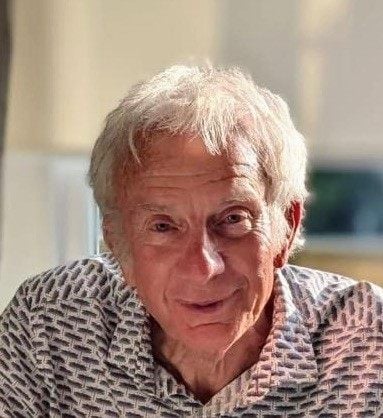

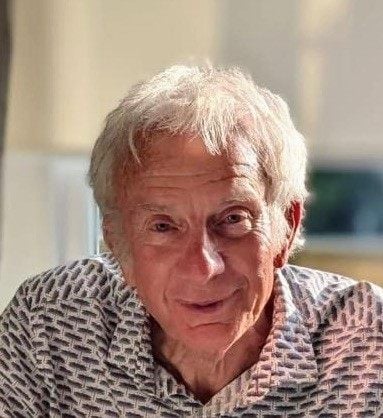

We speak to Roger Clough about his book Oldenland, a lifelong interest in ageing, and theory vs. practice when it comes to old age.

We speak to Roger Clough about his book Oldenland, a lifelong interest in ageing, and theory vs. practice when it comes to old age.

Roger Clough regularly finds changes to his body connected with his advancing years.

Only a couple of days ago, the 83-year-old found a pronounced line running the length of the inside of his hand. It’s Dupuytren’s disease – or Dupuytren’s contracture – a thickening of the connective tissue between the palms and fingers, which can cause the fingers to bend towards the palm.

While this uncomfortable symptom hasn’t occurred for Roger, his hands are increasingly affected by arthritis - as is his lower back. Meanwhile, memory issues mean he’s not sure which of the books in his collection he has already read, until a plotline or a turn of phrase reminds him partway through; and his wife, Ann, has pointed out he’s beginning to develop a slight stoop. Roger was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2019, though, after treatment, these days his PSA count is reassuringly low.

These changes and ailments, Roger suggests, are part and parcel of travelling in ‘Oldenland’, the name he uses to describe the metaphorical country that is old age – a place he’s spent his life studying, as a former Professor of Social Care and one-time trustee of Age UK Lancashire, while now putting theory into practice as a bonafide older person.

These changes and ailments, Roger suggests, are part and parcel of travelling in ‘Oldenland’, the name he uses to describe the metaphorical country that is old age – a place he’s spent his life studying, as a former Professor of Social Care and one-time trustee of Age UK Lancashire, while now putting theory into practice as a bonafide older person.

Roger and Ann have lived in a retirement village in the Peak District for the past seven years, giving Roger ample opportunities to explore the landscape of the nearby rolling hills, which may also have conjured the concept of ‘Oldenland’.

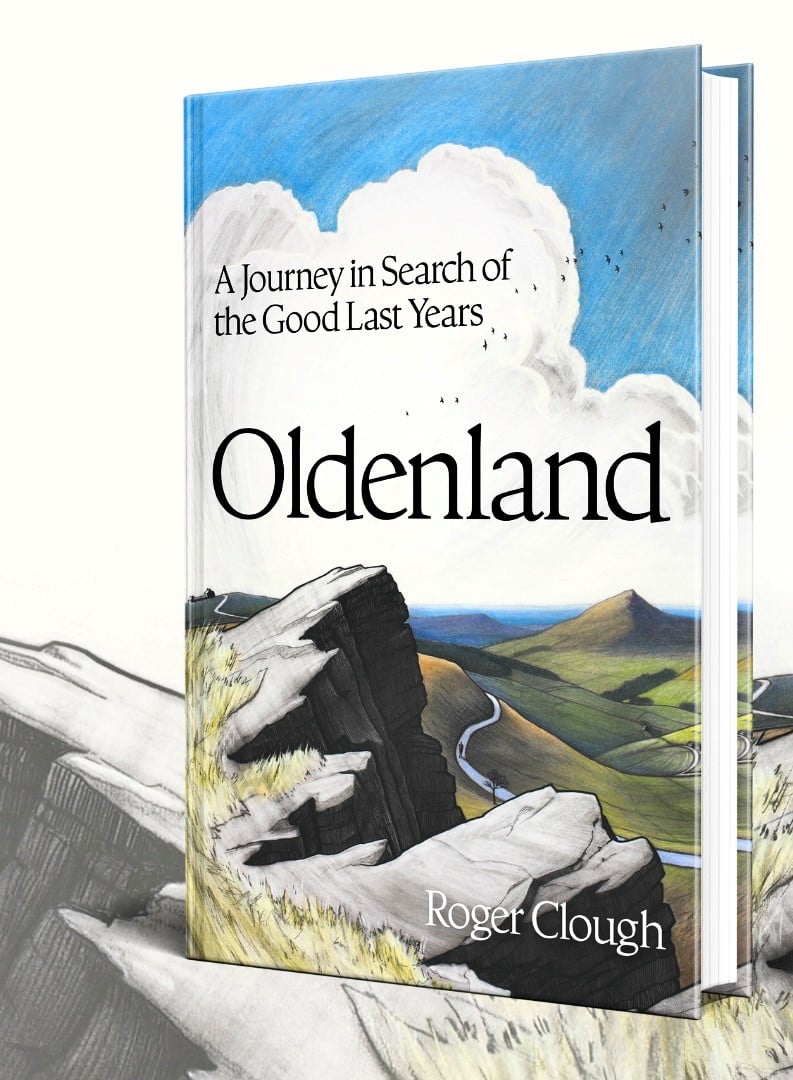

Oldenland is also the title of his book, which was some 25 years in the writing and is subtitled ‘A Journey in Search of the Good Last Years’. It’s a book that spins a lot of plates. It’s part memoir, chronicling Roger’s experiences studying the lives of older people, as well as his own ageing and that of his father, a Methodist minister, who died at the age of 101; and it’s part meditation on navigating later life once it arrives – or, rather, when we arrive at it like a destination.

Like many important things in life, Roger’s studious fascination with older people began by accident. Roger had started out working in ‘approved schools’, special schools for young people who had committed crimes or were deemed to need care and protection. Having applied for a job at Bristol Polytechnic as a lecturer on a newly set up course to help managers of residential homes develop their skills, Roger discovered at the interview stage that the course in question would be for staff working with older as well as younger people.

“I had to tell them that I didn’t have the experience and knowledge of working with adults,” recalls Roger. “But the chair of the interview panel said that they wanted someone able to use the existing theory about practice in residential homes with young people – and develop theory for working with other age groups.” He nevertheless got the job.

In the years since, Roger has held the Chair of Social Care at Lancaster University, has published eight books and contributed to research papers. Some of these papers included the collaborative research that went into a series of guides produced while Roger was a trustee at Age UK Lancashire, with titles such as ‘A dialogue with older people about what would help them lead fuller lives.’

I began more and more to think of growing old as the crossing of some sort of frontier.

Roger originally intended to call his latest book ‘Coming of Age: Living with an Old Me’, though ultimately thought better of it as the term ‘coming of age’ is more readily associated with adolescence. “I can’t really recall how exactly I came upon the title Oldenland,” admits Roger. “It may be because as a teenager I used to read a lot about exploration, of [John] Hunt exploring Everest, or [Jacques] Cousteau’s underwater exploration. I don’t know why, but I began more and more to think of growing old as the crossing of some sort of frontier.”

Somewhat philosophically, then, Roger looks at life as a journey. “[Life is] a meandering – stopping and pausing and being taken aback,” explains Roger. “It’s finding a way to keep going. I know there’s an ending, but I don’t know when it’s coming or how I’ll be at the ending. I want to live the years I have left with the reality that there’s not all that long to go – and how will I do that?”

Roger is keen to stress what Oldenland isn’t as much as what it is. It is not, he says, a book about keeping old age at bay, as that’s an impossibility, though he advocates making the lifestyle changes that will maximise the chances of enjoying a ‘better’ later life, as illustrated by Age UK's Act Now, Age Better campaign. Nor does the book examine what it means to have ‘a good death’, a notion that’s been explored elsewhere by others. And it doesn’t aim to answer all the questions about being old, because, as with everything else, those answers change from person to person. Instead, it finds Roger asking himself questions, therefore inspiring us to ask questions of ourselves, about how best to spend our last years.

A walk last year, as Roger neared completion of the book Oldenland, helped him reflect on how he intends to spend the time he has left. On an unusually sunny morning, he left the apartment he shares with Ann. He walked the way he had so many times before – passing the horses in the fields, through the woods, and around a small lake with nearby seating. For some reason, Roger looked at the seats on that day, perhaps drawn by how dishevelled they’d become from rust and leaves. Clearing the debris from one of them, Roger spotted an inscription carved into the wood – ‘Enjoy today’.

We don’t have to measure ourselves against other people’s ageing, or against the ideals of other people who tell us how we should live.

They’re words we should all try and live by, of course, whatever our age. Roger certainly does, and that’s his biggest takeaway from writing Oldenland: that he’s living with the reality of what, and who, he is now, enjoying the beauty to be found in the everyday – or, as Roger puts it, ‘immersed in the landscape of my life’.

“The idea that I've developed in the book is that of carving our ageing from the reality of our bodies and from the reality of our lives,” explains Roger. “We don’t have to measure ourselves against other people’s ageing, or against the ideals of other people who tell us how we should live. We have to look at ourselves and ask, ‘How do I want to live?’”

“The idea that I've developed in the book is that of carving our ageing from the reality of our bodies and from the reality of our lives,” explains Roger. “We don’t have to measure ourselves against other people’s ageing, or against the ideals of other people who tell us how we should live. We have to look at ourselves and ask, ‘How do I want to live?’”

Roger gives one last example of how one might choose to live. In the book, he quotes from a woman who had spent her life working in gerontology and now, in her own old age, was asked what advice she would give. ‘Go on becoming’ is her suggestion – it’s what we’ve done throughout our lives, so why should it stop?

“Our lives aren’t over,” says Roger. “Whatever has happened has happened to us, is happening, will happen. Old age offers us an opportunity - an opportunity to live.”

Actor Richard Durden and director James Marsh discuss Age UK’s ad campaign about we need to change how we age.

Economics and ageing mutually affect one another. This relationship is brought up to date in a new series of books.

Robin Lloyd-Jones remains as busy as ever in his eighties. In his new book, he meets others thriving in later life.

A fascinating new book compiles interviews with 28 older people to help change perceptions of ageing.